The State of Geography: Data and Trends in Higher Education

By Mark Revell and Mikelle Benfield

This year, AAG debuts The State of Geography report, presenting trends and indicators in post-secondary geography education in the United States. This report uses Classification of Instructional Program (CIP) codes, established by the National Center for Educational Statistics, to provide a snapshot of geography degree conferral patterns at the undergraduate and graduate levels. These data help identify trends and areas in need of additional attention, such as decreasing degree conferral in geography, racial and gender diversity across the discipline, and more.

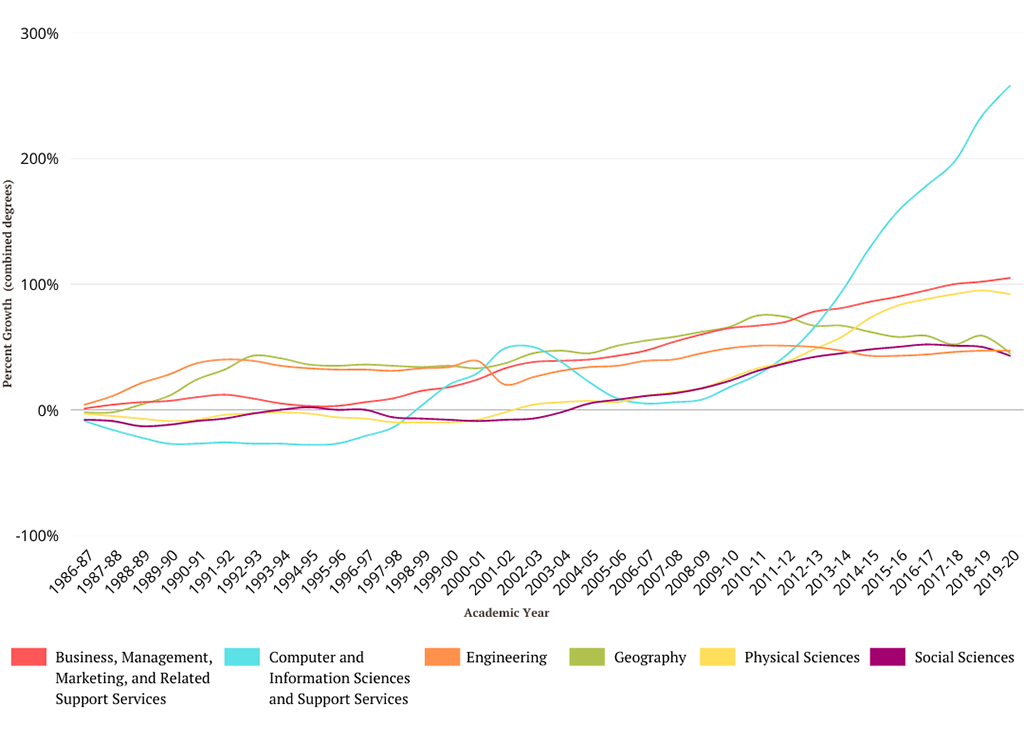

Recent changes in geography majors and graduation rates observed in this report take place against a broader backdrop of change in higher education, where uneven or declining growth in enrollments and degrees has taken place in numerous majors since 2012, and has been aggravated more recently by COVID-19. Our findings indicate a similar slowing of the robust growth in geography majors that began in the 1990s and peaked in 2012. The overall number of geography degrees has steadily declined since then, tracking with declining degree conferrals in many other disciplines, with the greatest impact felt in the social sciences and humanities, and at the undergraduate level. The trends for post-graduate degrees are more encouraging, with steady growth until very recently, almost certainly due to the impacts of COVID-19.

Geography by Many Other Names

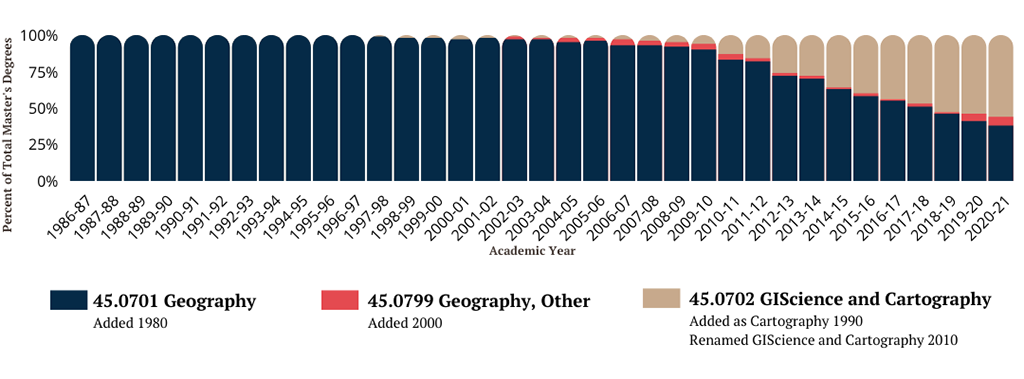

This report only captures trends for the six CIP codes that are currently related to geography, acknowledging that geography is also interdisciplinary and embedded in other disciplinary studies not clearly addressed by CIP codes. As new codes have been added over the years, we can see trends in disciplinary growth. In particular, GIScience and cartography degrees take up a larger proportion of current degree conferrals, particularly among master’s degrees. The proportion of GIS-related degrees is less dramatic at the bachelor’s and doctorate levels.

Reviewing CIP categories that have been added since 1980 yields insight into directions for the discipline. Three categories that are used most often date from, respectively, 1980 (Geography), 2000 (Geography, Other), and 1990/amended 2010 (GIScience and Cartography was Cartography from 1990-2010). Three additional categories created in 2020 have yet to be widely adopted, but identify known directions for geography practice: Geospatial Intelligence, Geography and Environmental Science, and Geography and Anthropology.

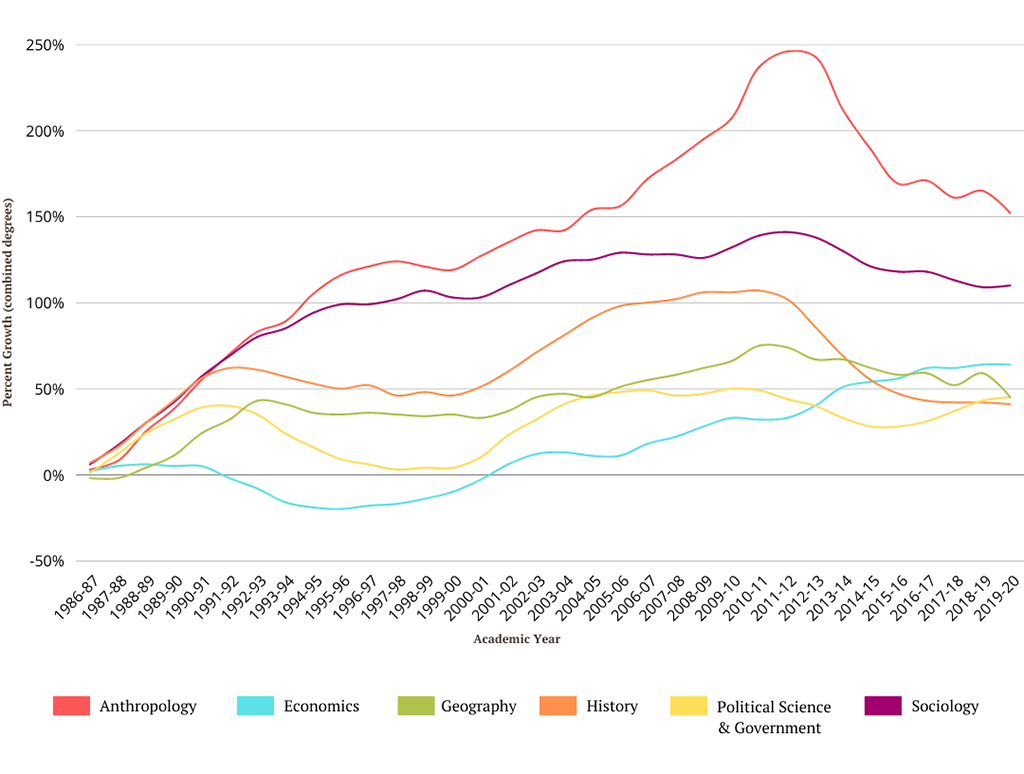

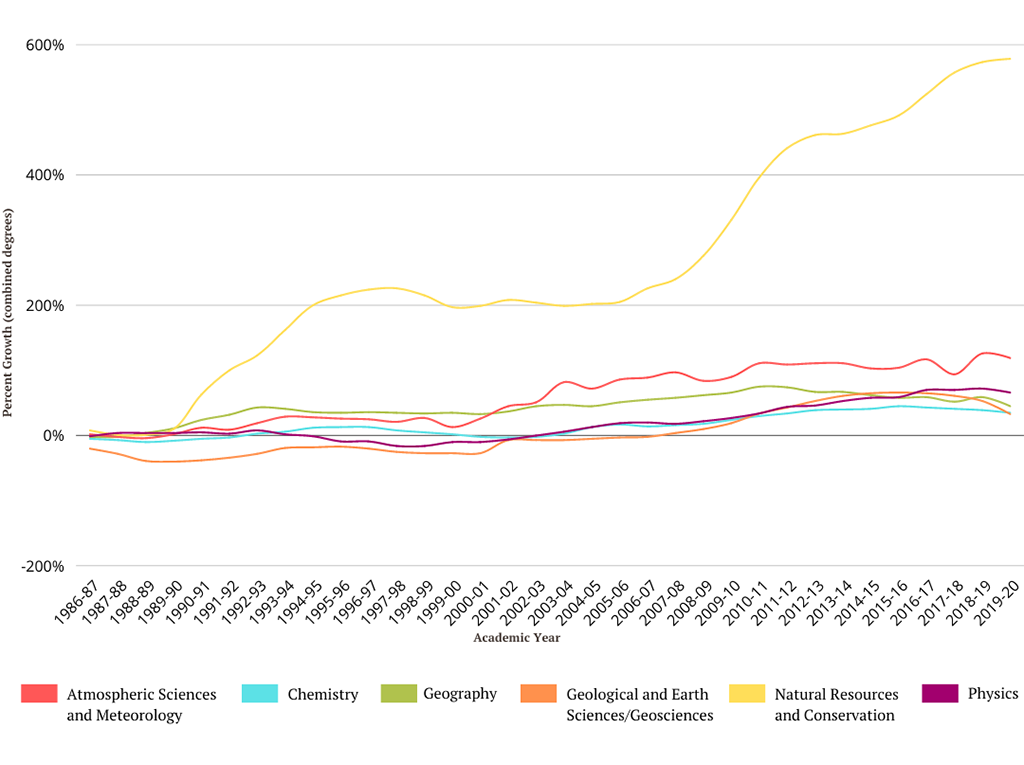

While the interdisciplinary nature of geography makes it widely appealing for study, it also makes the discipline a challenge to track due to the variety of non-geography CIP codes that departments can apply to their programs. For example, GIScience programs may use a computer science CIP code; physical geography may be classified through a natural sciences CIP code. The reason behind the choice of codes by program coordinators could range from codes that are better suited to visa programs to choosing high-growth non-geography CIP codes more likely to be favored by college administrations. In fact, AAG’s Guide to Geography Programs in the Americas already notes some CIP codes used by geography programs that were not included in this initial report, such as public health. Then, too, geography is being taught in other programs that are experiencing very high growth, such as atmospheric sciences, natural resources and conservation, and computer science and IT. These could be masking geography study, or could represent combined programs and departments.

Minding the Undergraduate Gap

Along with geography degrees at all levels, undergraduate degrees climbed steadily from just over 3,000 in 1986 to peak at roughly 5,000 in 2012. Growth has declined since then, reaching the level last seen thirty years ago at roughly 4,000 degrees conferred. When compared with all social and physical sciences, however, The State of Geography report found that geography has held its own, with a similar rate of growth to the combined rates for all social and physical sciences. Notably, natural resources conservation is the top physical science degree, and growing swiftly. This is a relevant finding to the capacity of geography studies to appeal to undergraduates, since spatial skills are indispensable to natural resources conservation. Almost all the sciences have experienced a dip in degree conferrals since 2008, and most lag far behind fields such as business management, marketing, computer sciences, and engineering. Part of this is likely the fallout from the Great Recession: The share of students majoring in social science and humanities degrees dropped steadily between 2008 and 2018, while the share of majors perceived as “recession-proof” grew.

In short, geography as a major makes a good showing within both families of science to which it has affinities. This indicates the enormous opportunity that lies in breaking geography out of silos and rethinking the breadth of its appeal to undergraduate students. In fact, Stoler et al. found in their 2020 study of student preferences that the actual word ‘geography’ rated far lower in undergraduate students’ minds than words suggestive of many geographic focus areas, such as ‘environment’ or ‘sustainability.’ The news about conventional geography degrees for undergraduates is sobering, and the discipline’s influence among college students seems far from waning.

Graduate Study Strong Despite Setbacks

While the net number of bachelor’s degrees conferred has grown by only one-third since 1986, effectively falling from historical highs to 2000-era levels, graduate studies grew by almost 100% (96% and 98%, respectively). Since 2016, however, graduate degrees have dipped sharply along with other disciplinary degrees in social or physical science compared with other disciplines, possibly a partial consequence of economic factors that are now aggravated by COVID-19.

Among the comparison fields in the report, geography graduate studies outperform virtually all other social sciences we examined at the graduate level when it comes to percent growth: they are second only to economics at the master’s level, and the number one choice at the doctorate level among the social sciences we compared. Among the physical sciences we compared, geography is second only to the rapidly growing field of natural resources and conservation at the master’s degree level (the same scientific field that has also greatly grown in undergraduate degrees). Doctorates in geography are outpaced by those in three physical sciences that all have close affinity with our discipline: natural resources and conservation, geology, and atmospheric science. It is worth asking why, if geography is such an attractive post-graduate degree, it has less traction among undergraduates. Are many geographers drawn to the discipline too late to change majors for their bachelor’s degree? Does the major even exist at their college? A student cannot earn a geography degree if none is available. Bjelland (2004,) found that only 7% of undergraduate liberal arts colleges offered a geography degree. For their part, the state university systems have made program changes since 2008, including combining or eliminating programs, due to increasing budget pressure and austerity. These changes yielded many more hybrid departments that may not explicitly recognize their geographic components (this is especially true in departments of urban planning and environmental science).

Notes on the Future

The overall decline in growth in geography degrees in the U.S. in recent years, especially among undergraduates, is concerning. Yet the relative strength in advanced degrees demonstrates staying power for the discipline, even at a time when so many disciplines and degrees are also declining. This could indicate that geography, often referred to as a “discovery” major, is resonating with students once they have discovered the field. Additional promising news, although outside the scope of this first report, is the apparent growth among associate degree geography or GIS programs at community colleges. There are now 210 community colleges in the United States that grant associates’ degrees in geography and GIS, compared with an estimated 158 in 2018. Shabram and Housel have found that many community colleges are “agile and demand-driven,” responding to the growing, unmet workforce need for spatial skills, noted by Solem et. Al. (2008).

Geography is also better positioned as a STEM science in future: the Geography and Environmental Studies CIP offers an important chance to increase geography’s visibility in this popular scientific area. Similarly, the Department of Homeland Security recent added Geography and Environmental Studies to its list of STEM degree programs.

These new developments can contribute to heightened awareness of geography, as well as better understanding of its power as a major and a career choice.

Note: The State of Geography Report also covers the conferral of degrees by race, ethnicity, and gender. These dimensions are crucial to a full understanding of the momentum of the discipline, and will be covered in future articles.

Get Involved in the Next State of Geography Report:

We look forward to further expanding on our findings in the State of Geography Report in the future, with data from a variety of sources, including NCES, AAG surveys, and AAG member expertise. We welcome questions, ideas, or suggestions about the findings at data@aag.org.

Further Reading

Bjelland, M. (2003) A place for geographers in the liberal arts college? The Professional Geographer, Vol 56, Issue 3 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0033-0124.2004.05603001.x

Revell, M. Community colleges are changing the landscape of higher education. (2021) ArcNews, Fall. https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/community-colleges-are-changing-the-landscape-of-geography-education/

Shabram, P,, and J. Housel, (2021) Building a partnership to build a pipeline for geographers. New Directions for Community Colleges, 194 Sum. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cc.20453

Solem, M., I. Cheung, M.B. Schlemper. (2008) Skills in professional geography: An assessment of workforce needs and expectations. The Professional Geographer, Vol. 60, Issue 3. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00330120802013620

Stoler, J. D. Ter-Ghazaryan, I. Sheskin, A.L. Pearson, G. Schnakenberg, D. Cagalanan. (2021) What’s in a name? Undergraduate perceptions of geography, environment, and sustainability keywords and program names. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. Vol 111, Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1766412

View the report