The Mental Health Challenge or Relieving Anxiety and Depression for Students and Faculty

About 18 years ago, one of my Masters students calmly mentioned that she had been undergoing a tremendous amount of anxiety, and had seen a doctor about it. I was floored! This particular student exemplified “no drama.” She was motoring through her Master’s thesis research and writing while effectively assisting me on one of my research projects. To think that Carol (not her real name) was suffering this sort of debilitating stress was a revelation. And then she said, “But Dave, everybody I know is suffering.”

About 18 years ago, one of my Masters students calmly mentioned that she had been undergoing a tremendous amount of anxiety, and had seen a doctor about it. I was floored! This particular student exemplified “no drama.” She was motoring through her Master’s thesis research and writing while effectively assisting me on one of my research projects. To think that Carol (not her real name) was suffering this sort of debilitating stress was a revelation. And then she said, “But Dave, everybody I know is suffering.”

I remember stress from college, graduate school and as a professor. High levels of tension were considered a badge of honor—some sort of endurance test—but these types of “masculinist” environments can leave some people unnecessarily wounded. Five years ago, past-president Mona Domosh described how her early experience of job uncertainty and loneliness opened up bouts of depression. The inability to talk about these issues only prolonged her despair.

Far more undergraduates report severe psychological disorders to counselors, including depression, anxiety, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts, eating problems and substance abuse. Stress begins early, as high school students suffer from “achievement pressure,” overcoaching, and a need to load college applications with all manner of activities and plaudits.

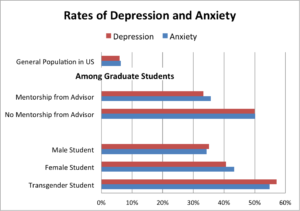

Graduate students can be overwhelmed by mental distress. A recent survey of mostly Ph.D. candidates showed that 39 percent were moderately to severely depressed, with slightly higher rates for women and much higher rates among transgender students. These incidences greatly surpass the general U.S. population, which are within a percentage point or so of most other countries. Students are hurting. The reasons behind their stress are obvious: overwork, strained relationships with advisors, feeling a lack of support, worries about the future, and a reluctance to talk about these problems. In one tragic case, a graduate student committed suicide because he felt bullied into publishing work that was incorrect.

Faculty also suffer. This is especially true of those still awaiting full-time employment, working under precarious conditions as adjuncts. Yet professors everywhere contend with pressures to produce as the bar reaches ever higher. Lawrence Berg and others liken this to the anxiety instilled in the neoliberal university, where conditions of competition, inequality, and economization of labor prevail. Faculty may have once been free to define their own scholarship, but there is now a greater focus on differentiating winners from losers. A report from the U.K.—where this economization of faculty is further along—discusses the unrelenting pressure to procure grant money and to publish, publish, publish. The increasing use of metrics all around only aggravates the burden.

Mental health challenges, and the tensions that produce them, will only worsen. It seems that we live in a more competitive age. Social media exposes too much information, flagging our inadequacies and failures. I can only shudder at the thought of how people applying for graduate school and for faculty positions can witness, in real time, the experiences of every other applicant.

Breaking the culture of silence is critical. People need to feel they can talk to other people, in confidence, about their problems. Sometimes professional therapy is absolutely required. But pressure can often be relieved through sympathy, reassurance, and the realization that others have many of the same struggles. Beyond this, universities and colleges can provide accessible and affordable mental health care, put in a robust referral system, and make it easier for people to take a leave if so indicated. The AAG has initiated a mental health affinity group with the charge “to explore how the organized practices of the academy are implicated in the current state of mental health among students, faculty and staff across university campuses and in doing so, consider ways that we might create healthier environments.” [AAG login required]

A toxic academic culture that looks the other way when students and colleagues are harassed engenders feelings of worthlessness and saps motivation. Cases in geography and in academia as a whole have exposed the perniciousness of what used to be acceptable behavior. The AAG has developed its Harassment Free guidelines, and we seek better ways to address the problem at conferences and in workplaces. But of course this only covers a small part of the terrain. Eradicating harassment wherever it occurs should be the goal.

Departments should instill a culture of friendliness. In my view, there are few people so important, or who are engaged in such significant research, to be allowed to get away with being nasty or even indifferent to others. Yet we seem too willing to forgive jerks, particularly those deemed “successes” because they are well-known in their field or bring in a lot of grant money. Such values, whether propagated by chairs, advisors, professors, or fellow students, are inimical to a healthy academic culture. People should observe certain norms of civility, treating everyone with a level of respect and also providing a level of accessibility. While it is hard to change human behavior and everybody lapses once in a while, our collective mental health would improve tremendously if people were just a bit kinder.

So much of the stress of academic life comes from the high incidence of rejection. Students and junior professors are under the gun to publish articles and get grants. They look around and compare themselves to what seems an unending string of successes. But much like Facebook displays a carefully curated collection of congratulations, cute children, and exotic travel experiences, a senior professor’s cv does not represent the real struggles she has endured. A so-called “failure cv”—proposed a few years ago—is a way to remind us of the hard and often unrewarding work we do. If made public, it also shows that there are no glide paths to success.

Professors must set standards and educate students in the best way they know, and these challenges can be made easier with clear access and instructions. I recall too many professors who would spring something on their class, not for any purpose but because they had not gotten their act together. A student’s well-being is supported by instructors who are prepared for each class, show reasonable flexibility, and express sympathy and openness. Yet a recent survey showed that only half of college graduates reported having any meaningful relationship with faculty or staff. I always try to remember that many students worry about contacting their professor, or intruding on her time. Closing the door, either literally or figuratively, because more important work must be done sends a signal of relative value. Of course it is necessary to sequester ourselves at times, but we must make sure we are available, responsive (yes—even on weekends when the need and anxiety on the other side is great), and caring.

To that end, we need to publicize our understanding, sympathy, and availability. Last year, a colleague in another program sent around a message that she suggested we share with our students. I and several other faculty followed up with emails to students saying we understood that the end of the semester can be stressful, that it was important for students to take care of their mental and physical health, that we would be available to speak anytime to anyone with problems, and to refer them to someone who could help. The email really struck a chord. Students felt that they were not quite so alone.

Mental health is complex, and some issues are severe enough that they need to be tackled professionally. But would it not help everybody, those simply stressed and those truly in despair, if they could feel the meaning behind these words? We are here. For you.

— Dave Kaplan

AAG President

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0060

Data from:

World Health Organization (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Evans, Teresa M, Lindsay Bira, Jazmin Beltran Gastelum, L Todd Weiss & Nathan L Vanderford (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology 36, 282–284