Essential Geographies of New Orleans Music

Part 1: Congo Square, Atlantic Exchange, and the Emergence of Jazz

New Orleans is a meeting ground. Situated at the confluence of the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, the city connects North America’s most expansive riverine network with the vast Atlantic basin. Its strategic location has long attracted diverse peoples and ideas, whose collaborations have forged extraordinary cultural, economic, and ecological innovations. Prominent among those novel expressions, music remains central to New Orleans’ sense of place. This essay, offered in two parts, surveys the cultural and historical geographies of music in New Orleans. It outlines a rough chronology of the innovative musical cultures that coalesced and continue to proliferate in New Orleans, emphasizing both the singularity of the city’s cultural production, as well as its fundamental connections with the French, Hispanic, and Black Atlantics.[1] This geographical treatment will, I hope, prime attendees of the 2018 AAG Annual Meeting to indulge in New Orleans’ rich musical (and other performative) cultures on display at countless clubs, bars, restaurants, parties, parades, and street corners, as well as the French Quarter Music Festival. Overlapping with the AAG conference and free of charge (!), the lively outdoor fête showcases some of the region’s most celebrated acts and styles. In this first of two parts, I treat the city from its founding in the early-eighteenth century through the emergence of jazz in the early-twentieth century, providing historical-geographical context for the distinct and diverse musical cultures emanating from New Orleans.

New Orleans and its musical cultures are perhaps best understood through the city’s complex connections to the African diaspora, its experiences within the French and Spanish Colonial Empires, and its relations to fluvial networks and ports throughout the mainland Americas and the Caribbean. After founding the city in 1718, France ceded New Orleans to Spain in 1762. The city spent four formative decades under Spanish control, undergoing significant demographic, urban, and economic growth. Napoleonic France briefly regained control of the city in 1803 before selling it to the United States just three weeks later in the Louisiana Purchase. As the colony changed hands over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a steady flow of enslaved Africans continually replenished profound African influence in New Orleans and its environs. Those fundamental influences continue to manifest in the city’s rich cultural and economic development, especially by way of its music.[2]

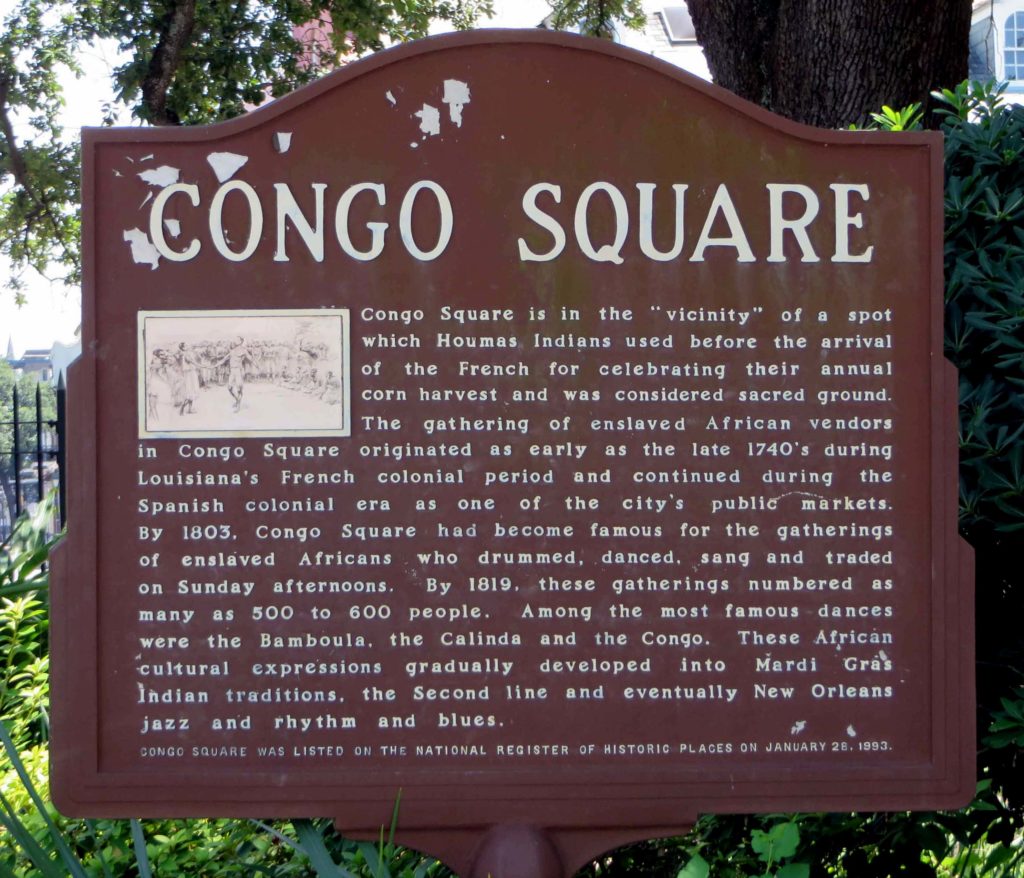

The historical-geographical hearth of musical culture in New Orleans (and, it could be said, of the US as a whole) is Congo Square—the first and only sanctioned gathering place for enslaved people in the antebellum United States—beginning as early as the 1740s (Figure 1). Located just outside of the original city walls, near the grounds of the Tremé Planation, Congo Square originated as a Sunday market where enslaved Afro-descendants and indigenous people gathered to trade in goods they themselves had grown, gathered, and hunted. The weekly gatherings soon became an extraordinary venue for cultural exchange where hundreds of people mingled, cooked, drummed, worshipped, danced, and sang. Spirituality was fundamental in those musical and rhythmic expressions, as drumming remains essential in the syncretic religions that developed among Afro-descendants in the New World, among them Vodun in Haiti, Santeria in Cuba, and Voodoo and Hoodoo in New Orleans.[3]

Beginning in the French period, Congo Square and its weekly assemblies survived and evolved through Spanish control and later the city’s integration into the United States. By the early nineteenth century, visitors documented crowds numbering more than 500 practicing distinct forms of African drumming, singing, and dancing. The humble outdoor market became a historic nexus crucial for the preservation of African cultural forms, as well as the eventual creation of novel hybrids mixing, as just one example, Senegambian-style banjos with drumming from the Kongo. Congo Square thus remains an important site of African-American cultural and economic resistance where enslaved people of African descent, despite the horrific brutalities of slavery, laid the rhythmic foundations for what eventually became blues, ragtime, jazz, country, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, hip hop, and countless other American musical genres. As prominent New Orleans jazz musician, educator, and advocate Wynton Marsalis proclaimed, “The bloodlines of all important modern American music can be traced to Congo Square.”[4]

While many New Orleans traditions trace their beginnings to Congo Square, the various groups collectively known as Mardi Gras Indians maintain a particularly firm link to the traditions forged there. Melding West African, Indigenous American, and European Catholic traditions, the Mardi Gras Indians celebrate the pre-Lenten Carnival (and a few other dates) by creating, costuming, and parading in lavish handmade regalia adorned with thousands of sequins, beads, and feathers (see Figure 2). Keepers of extravagant musical and material traditions traceable to Yoruba and Haitian Afro-creole antecedents, the Indians remain influential community leaders in many neighborhoods of New Orleans. (See Part II of this essay for more on the Indians’ musical influence).[5]

New Orleans’ distinct musical traditions began to coalesce during the Spanish period (1763-1803) when colonial trade and administrative networks linked the city with Vera Cruz, Tampico, and especially Havana, then the seat of the Spanish American colonies. Military-style marching bands provided the basic instrumentation and arrangements for the region’s music, as well as public spectacles. When Spanish Governor Miro received a delegation of Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian chiefs in 1787, he wooed them with a ballroom dance and an extravagant military parade.[6]

The following decade, refugees fleeing the Haitian (Saint Domingan) Revolution—roughly equal thirds White creole, enslaved, and free people of color—began streaming into New Orleans. Bringing with them African-inspired spiritual and musical traditions forged in the French Atlantic, the refugees doubled the city’s size by 1810. To keep up with the abrupt population growth, New Orleans quickly expanded its footprint north of the original city into former lands of the Tremé plantation, creating the faubourg (neighborhood) of the same name, where many Haitians and other émigrés eventually settled.[7]

Born in New Orleans, antebellum piano prodigy Louis Moreau Gottschalk grew up studying music with his grandmother Bruslé and her enslaved nurse Sally, both natives of Saint Domingue, before travelling widely in the Caribbean and Latin America. His piano composition “Bamboula, Danse des Nègres” (1848) drew on African-inspired folk traditions from the Antilles, and melded seamlessly with the rhythms of Congo Square. Written in Martinique in 1859, his “Ojos Criollos, Danse Cubaine” (Creole Eyes, Cuban Dance) blended Afro-Cuban rhythms with European melodies to foreshadow ragtime by three decades. By the mid-19th century, many widely popular musical styles—from minstrel show tunes, ragtime, and cakewalks to Cuban habanera, rumba, and son clave—all shared syncopated two-hand piano riffs made popular by Gottschalk. Those rhythms served as a foundation for later styles, including jazz, and live on not only in New Orleans’ second line parades and Mardi Gras Indian gatherings, but also the comparsa and conga processions of Cuban Carnival.[8]

Essential to the city’s musical traditions, brass bands were already integral to public life in New Orleans by the early nineteenth century. In 1838 the daily Picayune proclaimed a “mania in this city for horn and trumpet playing” derived from military bands and processions. Following the Civil War, that instrumentation combined with African-inspired funeral celebrations to lay the groundwork for New Orleans jazz funerals and second lines. Adding to the mix were post-abolition waves of African-American workers who migrated to the city in search of economic opportunities, bringing along their canon of work songs, spirituals, and blues from the Mississippi Delta. There the sacred call-and-response musical aesthetic of the Plantation South encountered the widely popular dance craze known as ragtime, and together began filtering through New Orleans’ traditional brass instrumentation and syncopated African rhythms.[9]

By century’s end, changes in the city’s legal frameworks would unwittingly galvanize the music scene in New Orleans, and provide the final ingredients for the musical gumbo that would coalesce as jazz. After the landmark Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson codified racial segregation into a strict binary, mixed race creole musicians found themselves officially classified as Blacks. An unforeseen consequence of that terrible ruling was the integration of the city’s brass bands, unifying creole musicians and their classical training with the more freewheeling styles of the city’s Black blues musicians. The following year, in 1897, the New Orleans city council created the city’s red light district where prostitution, drugs, and gambling were regulated and confined. The rough-and-tumble Storyville district provided steady gigs for brass bands and piano players at the end of the nineteenth century. Located in the Faubourg Tremé just two blocks from the site of Congo Square, the district became ground zero for a revolution in American music (Figure 3).[10]

Emanating from New Orleans around the turn of the twentieth century, the novel improvisational styles that would collectively become known as jazz emerged from essential connections with the Mississippi Delta, Latin America, and the Caribbean. First visiting the city as part of the New Orleans World’s Fair of 1884–85, several Mexican bands and musicians became legendary for their lasting effects on the city’s musical cultures, including the introduction of the saxophone, bass plucking, and original compositions. Members of the Onward Brass Band, then among New Orleans’ most prominent marching bands, traveled to Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Among them were trombonist Willie Cornish and alto horn player John Baptiste Delisle, musicians that also played with Charles “Buddy” Bolden, a (the?) forerunning jazz musician. By the turn of the 20th century, jazz pioneers Bolden, Joe “King” Oliver, and Jack “Papa” Laine were collaborating with musicians with strong ties to Cuba, such as Manuel Pérez and Manuel Mello.[11]

The second generation of New Orleans jazz musicians could still discern the Afro-Latin influences fundamental to the jazz sound. Citing what he called “little tinges of Spanish,” New Orleans pianist Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, himself a descendant of creole Haitian émigrés, credited habanera rhythms as essential elements in New Orleans jazz. Another member of the second generation, the great Louis Armstrong, got his start in Storyville where he played in bands led by Kid Ory and King Oliver. Their repertoire included “New Orleans Stomp,” a popular dance tune steeped in complex Afro-Caribbean rhythms and time signatures.[12]

Jazz thus emerged in New Orleans as a delicious gumbo of ragtime, Delta blues, and the diasporic rhythms of the Afro-Caribbean. Despite continuous growth and innovation, most New Orleans music still derives from fluid blends of syncopated rhythms celebrated in Congo square and countless Afro-Caribbean communities with Eurasian instrumentation and melodic forms. The genius of New Orleans’ music springs not from the spontaneous epiphanies of a few talented individuals, but instead crystallizes from the city’s fluid connections to other places. At the confluence of the French, Spanish, and Black Atlantic Worlds, New Orleans has long provided an inclusive venue for the integration of diverse cultural forms.

New Orleans will forever be associated with jazz, yet the soundtrack of the contemporary city is more complex. While people of all ages continue to enjoy an ever-expanding array of expressions falling under the jazz umbrella (e.g. Dixieland, trad jazz, Latin jazz, avant-garde jazz, jazz-funk, and various fusion sounds), New Orleans remains devoted to a grand diversity of musical genres and styles, such as brass bands, R&B, soul, funk, rock and roll, heavy metal, hip hop, bounce, and even zydeco—an upbeat Afro-French creole dance music from west of the Atchafalaya. In part two of this essay (coming early 2018) I discuss several of those musical traditions as they emerged in New Orleans since the twentieth century, with special emphasis on the artists and styles on display at the 2018 French Quarter Music Festival (Figure 4) that overlaps with the AAG annual meeting.

Further reading and listening: To begin your preparations for New Orleans, be sure to live stream WWOZ, New Orleans community radio and self-proclaimed “Guardians of the Groove.” For more on New Orleans music, see the works referenced in the notes below and the following resources: recordings posted online by the Smithsonian Folkways Magazine, a YouTube playlist of recordings of Mardi Gras Indians compiled by the Alan Lomax archive; and a YouTube playlist of New Orleans music compiled by the author. Finally, I cannot recommend enough A Closer Walk, an interactive website, map, and series of guided tours of the geographies of New Orleans music, sponsored by WWOZ and others.

— Case Watkins, James Madison University

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0013

[1] With those terms I follow a wealth of scholarship on the interconnected Atlantic Worlds, especially their connections to the African diaspora, the French and Spanish colonial empires, and the territories and communities they helped shape. See Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993). Douglas R. Egerton et al., The Atlantic World: A History, 1400 – 1888 (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007). William Boelhower, ed., New Orleans in the Atlantic World: Between Land and Sea (London: Routledge, 2010).

[2] Andrew Sluyter et al., Hispanic and Latino New Orleans: Immigration and Identity Since the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015). Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995).

[3] Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2008). Michael Crutcher, Tremé: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010). Freddi Williams Evans, Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2011).

[4] References in note 3. Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Impressions Respecting New Orleans: Diary and Sketches, 1818-1820, ed. Samuel Wilson Jr. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951). Quote on the jacket for Evans, Congo Square.

[5] Michael P. Smith, “Behind the Lines: The Black Mardi Gras Indians and the New Orleans Second Line,” Black Music Research Journal 14, no. 1 (April 1, 1994): 43–73. DOI: 10.2307/779458 Michael P Smith, Mardi Gras Indians (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1994). Richard Brent Turner, Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009).

[6] Charles Gayarré, History of Louisiana, Vol. 3 (New York: Redfield, 1885). William Schafer, Brass Bands and New Orleans Jazz (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977).

[7] Sublette, The World that Made New Orleans. Crutcher, Tremé.

[8] S. Frederick Starr, Bamboula! The Life and Times of Louis Moreau Gottschalk (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). Jack Stewart, “Cuban Influences on New Orleans Music,” Jazz Archivist 13 (1999): 14–23. Turner, Jazz Religion. Sublette, The World that Made New Orleans.

[9] Schafer, Brass Bands. Sybil Kein, “The Celebration of Life in New Orleans Jazz Funerals,” Revue Française D’études Américaines, no. 51 (1992): 19–26. Donald E DeVore, Defying Jim Crow: African American Community Development and the Struggle for Racial Equality in New Orleans, 1900-1960 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015).

[10] Al Rose, Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974). Charles Hersch, Subversive Sounds: Race and the Birth of Jazz in New Orleans (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). City leaders demolished Storyville in 1940 to make way for the New Deal era Iberville Housing Projects, which are currently being redeveloped as mixed-income apartments.

[11] Jack Stewart, “Cuban Influences on New Orleans Music.” Jack Stewart, “The Mexican Band Legend: Myth, Reality, and Musical Impact; A Preliminary Investigation,” Jazz Archivist 6, no. 2 (1991): 1–14. Jack Stewart, “The Mexican Band Legend–Part II,” Jazz Archivist 9, no. 1 (1994): 1–17. John McCusker, “The Onward Brass Band in the Spanish American War,” Jazz Archivist 13 (1998-1999): 24-35. Schafer, Brass bands.

[12] Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax, Music CD (Cambridge, MA: Rounder Records, 2005): Disc 6, Tracks 8 and 9. Stewart, “Cuban Influences.” Louis Armstrong, Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans (New York: Da Capo Press, 1986).