Program Profile: University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire – Department of Geography & Anthropology

In 2024, AAG recognized the Department of Geography and Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire (UWEC) with the AAG Award for Bachelor Program Excellence. We asked Ryan Weichelt, a UWEC alumnus and current department chair, what makes the program stand out. He shares three key reasons how the department continues to evolve and meet the needs of the students, workforce, and discipline: promotion of geography and collegiality across campus, pursuit of scholarship, and excellence in instruction.

Cross-Campus Collaboration

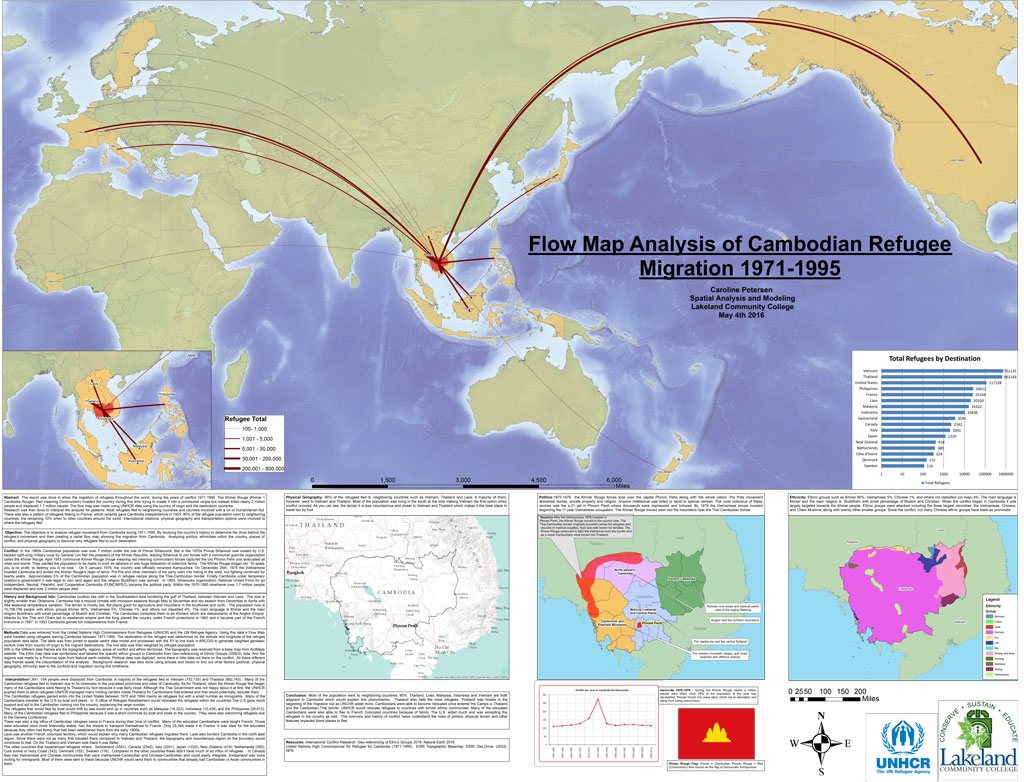

In 2014, the Department of Geography and Anthropology developed the Geospatial Analysis and Technology major to integrate geospatial technologies across disciplines in direct cooperation with public and private stakeholders, highlighted in a publication by Esri Press “Extending Into STEM: The Geospatial Education Initiative.” The major quickly gained momentum.

During this period, the department began to partner closely with the university to become a hub for geospatial technology and expand its reach into various programs on campus, including biology, computer science, and data science. Geospatial technology has distinguished the department on campus ever since, and facilitates significant research opportunities. For instance, faculty and students have collaborated with Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) to leverage geospatial technologies in understanding and improving healthcare across the country. The interdisciplinary nature of these technologies “has shown how geography can play a role in understanding healthcare and making [it] available for more people,” says Dr. Weichelt.

While the department’s largest major is environmental studies, the geospatial program has driven numerous cross-campus collaborations. Biology and geology students frequently enroll in numerous certificate programs, leading to new majors and fostering a collaborative academic environment. The geospatial technology program has opened doors for interdisciplinary research and attracted new students who wish to work in archaeology, climate science, resource planning, or conservation.

Pursuit of Scholarship: “Geography is Everything”

The department offers a diverse range of classes and Liberal Education (LE) core components, akin to General Education in other institutions. Dr. Weichelt expresses the department’s pride in the breadth of curriculum, encompassing physical geography, technology, and cultural studies. The versatility of courses enables staff and students to provide extensive service to the university, supporting its growth and attracting prospective majors.

This commitment to geography as an all-encompassing discipline underscores the departmental belief that “geography is everything.”

Cross-campus collaboration also attracts new students, supporting other department efforts, such as incorporating GIS into non-geospatial classes, and renaming introductory classes to clarify that they belong to a series: “Planet Earth, Human Geography,” “Planet Earth, Physical Geography,” “Planet Earth, Cultural Geography,” and so on. Equipped with three state-of-the-art computer labs, the department can offer students a state-of-the-art computing experience, with support from alumni grants and donations and the university, which provides geospatial lab modernization funds every two years. Students across the university can access these dedicated spaces to get direct experience with remote sensing, GIS, and other geospatial tools.

Fieldwork is also a critical component of UWEC’s curriculum. “Many of our classes require field components, not just the physical geography classes, [but also] those like tourism geographies, urban geographies, and Indigenous geographies courses,” says Dr. Weichelt.

Students have field work opportunities with their professors in the United States, internationally, or remotely. Dr. Harry Jol, for example, conducts ground-penetrating radar (GPR) research globally and recently took students to Lithuania to study Holocaust sites. Dr. Douglas Faulkner, a fluvial geomorphologist and recipient of the 2019 Gilbert Grosvenor Award, brings students to local rivers like the Chippewa, Eau Claire, and Red Cedar Rivers. Dr. Papia Rozario collaborates with colleagues across the U.S. on remote sensing and AI research, analyzing precision agriculture data obtained with drones.

A standout course, Geography 368, mandates 7 to 12-day field expeditions for all students. Even during the COVID-19 campus closures, students in the course adapted by researching sustainable city exploration via bicycles. Students also must complete 30 hours of community service before graduation. The geography club’s “Missing Maps” program allows students to apply their geospatial skills while fulfilling this requirement, making meaningful contributions to communities across the globe.

Excellence in Instruction: Strengthening Department Culture

Dr. Weichelt praises the numerous younger faculty members the department has hired in recent years. They help to foster a more cohesive and collaborative environment, enhancing the program’s longstanding tradition and continuously updating curriculum to address Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) issues, particularly how geographers and geography can contribute to solving these critical questions. This is upheld by an Anti-Racist Statement wrote and approved in 2020, in addition to the University’s EDI Goals.

As the state grapples with challenges to campus justice and equity initiatives, the department is using scholarships to help bridge gaps for diverse students, while adhering to new state regulations. For example, six first-year students interested in majoring in geography are eligible to apply for the George Simpson Incoming Student Scholarship, ranging from $1,000 up to $1,500.

Faculty are active in campus organizations and programs that advocate for diversity and inclusion such as the Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Sexuality Program and American Indian Studies. This commitment to inclusivity and support is mirrored in the department’s vibrant student life. From a strong geography club, welcome parties and celebrations, mentorship opportunities, and speaker series presentations, connecting with students “always been a tradition here.” The level of attention to maintaining and strengthening the department culture in turn strengthens the discipline and future geographers.

UW Eau Claire’s Department of Geography and Anthropology exemplifies excellence not only through its award-winning programs but also through its dedication to student success and inclusivity. By fostering a supportive and dynamic environment, the department ensures that its graduates are well-prepared to tackle the challenges of the modern world, making significant contributions to the field of geography and beyond.