Geographies of Bread and Water in the 21st Century

Geography is a big discipline, both in terms of its global purview and the wide spectrum of scholarly perspectives geographers bring to bear. We should not be shy about applying ourselves to some of the biggest and most complex problems facing the world. What could be a more critical problem then providing bread and water to support the planet’s population now and in the year 2050 when over 9 million people will depend on the finite resources of the earth for sustenance? This past month the United Nations held a High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development and issued its first tracking report on global sustainable development. U.N. officials noted that today approximately 800 million people suffer from hunger and 2 billion face challenges of water scarcity.

Geography is a big discipline, both in terms of its global purview and the wide spectrum of scholarly perspectives geographers bring to bear. We should not be shy about applying ourselves to some of the biggest and most complex problems facing the world. What could be a more critical problem then providing bread and water to support the planet’s population now and in the year 2050 when over 9 million people will depend on the finite resources of the earth for sustenance? This past month the United Nations held a High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development and issued its first tracking report on global sustainable development. U.N. officials noted that today approximately 800 million people suffer from hunger and 2 billion face challenges of water scarcity.

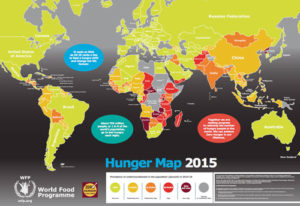

Of course, the challenges of food and water scarcity are not homogenously distributed across a “flat earth.” Looking at the 2015 – Hunger Map prepared by the U.N. World Food Programme, we can see an uneven geography where undernourishment afflicts less than 5 percent of the population in North America, Europe, Australia and considerable portions of South America and Asia. In stark contrast, across large swaths of sub-Saharan Africa greater than 25 percent to 35 percent of the population are undernourished. Similarly, the world is not flat when it comes to water scarcity. The U.N. World Water Assessment Map displays a geography that contains some elements of the Hunger Map, but also some important differences. According to the U.N. World Water Assessment Programme, water scarcity also afflicts much of sub-Saharan Africa, but water scarcity also extends in a broad stroke across Northern Africa, the Near East and into southern and central Asia as well. Areas such as northern Mexico and the adjacent southwestern United States and southeastern Australia are also experiencing water scarcity.

Of course, the challenges of food and water scarcity are not homogenously distributed across a “flat earth.” Looking at the 2015 – Hunger Map prepared by the U.N. World Food Programme, we can see an uneven geography where undernourishment afflicts less than 5 percent of the population in North America, Europe, Australia and considerable portions of South America and Asia. In stark contrast, across large swaths of sub-Saharan Africa greater than 25 percent to 35 percent of the population are undernourished. Similarly, the world is not flat when it comes to water scarcity. The U.N. World Water Assessment Map displays a geography that contains some elements of the Hunger Map, but also some important differences. According to the U.N. World Water Assessment Programme, water scarcity also afflicts much of sub-Saharan Africa, but water scarcity also extends in a broad stroke across Northern Africa, the Near East and into southern and central Asia as well. Areas such as northern Mexico and the adjacent southwestern United States and southeastern Australia are also experiencing water scarcity.

As if the current global food and water situation is not troubling enough, the prognosis for the future indicates even more challenges ahead. In 2009, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization produced in a hallmark report that concluded increasing human population size coupled with economic growth, urbanization and demands for high-quality food products will result in the need for a ~70 percent increase in agricultural productivity by 2050. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization this would require some 3 billion tonnes additional cereal production each year, as well as an additional 200 million tonnes of meat production. The U.N.’s estimates on future water scarcity are also not reassuring. The World Water Assessment Programme concludes that by 2025, some 1.8 billion people will be living in areas with significant water scarcity.

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change on agricultural productivity at 2050 are not entirely clear. As an example, in a 2012 review published in Plant Physiology, David Lobell and Sharon Gourdji suggested that even under pessimistic scenarios it is unlikely that net global declines in agriculture will occur at 2050. On the other hand, a 2014 study published in Nature Climate Change by Senthold Asseng and a number of co-authors including Charles Jones of the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland and Fulu Tao of the Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources of the Chinese Academy of Sciences concluded that with each additional degree of warming, global wheat production could decline by 6 percent.

The conclusions of the U.N. World Water Assessment Programme in terms of future water scarcity are concerning. Under current climate change scenarios, it is possible that close to 50 percent of the world’s population will be living in regions experiencing high water stress as early as 2030. Although the greatest number of regions likely to be afflicted by severe water scarcity lie in sub-Saharan Africa, there is little cause for those in highly developed countries to be sanguine. The Colorado River reservoir system upon which much of the Southwest receives water and hydroelectric power is already facing unprecedented low-water stresses. A recent paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society by Julia Vano and others, including Dennis Lettenmaie, now at the UCLA Geography Department, suggests that over the 21st century the river is likely to experience decades of flow significantly lower than observed in the 20th century when the reservoir system was developed.

Just as today, forecasts for the future of food and water resources indicate that regional variability will be a key feature of scarcity and a critical component in addressing global challenges. Geographers have helped lead the way in appreciation of this. Diana Liverman, now at the Department of Geography of the University of Arizona, pointed this out almost 25 years ago in her work such as that with Cynthia Rosenzweig, on “Predicted effects of climate change on agriculture: A comparison of temperate and tropical regions.” More recently, William Easterling, a geographer at Penn State, and his co-authors of the chapter “Food, Fibre, and Forest Products” in the 2007 International Program on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment provide important and clear elucidation of the spatial heterogeneity in the agricultural impacts of climate change. The food and water challenges are inherently geographical in nature and the spatial scales we need be concerned with range from the global to the national and down to the individual field. Considered from a biological and physical environmental perspective one can clearly see the role that agricultural geographers and geographical hydrologists, climatologists and pedologists can and have been playing. However, it will take more than that from our discipline.

Consider again the maps and reports that the U.N. has produced on hunger and water scarcity. If environment, in the form of climate or soils etc., were the sole determinant of hunger or water scarcity we would expect neat correspondence between food challenges and isotherms or isohyets etc., but that is not the case. Rather we see much spatial diversity in these patterns, which can be attributed to differing socioeconomic conditions. In some cases, countries with undernourishment rates of less than 5 percent, lie adjacent or close to countries with rates of more than 25 percent or greater than 35 percent. This is particularly true in Africa, but is also seen in parts of South America, Central America and Asia. Water scarcity also shows such national heterogeneity. The U.N. World Water Assessment is explicit in separating those regions, such as the American Southwest, suffering from physical water scarcity and those, such as sub-Saharan nations, suffering from economically induced water scarcity. Environment has a role in the geography of food and water scarcity, but clearly the causes arise from a more complex amalgamation of environment with socioeconomic factors.

Famine in Africa today chillingly illustrates the complexity of the food security problems we face in terms of causal factors and solutions. According to the U.N., a current climatic drought, coupled in some regions with the occurrence of damaging flood events, has placed as many as 18 million people in need of food assistance in countries such as Malawi, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. At the same time, civil war in South Sudan is a major contributor to a food crisis facing almost five million people while in Nigeria the barbarity of Boko Haram terrorists is a major factor in placing over 4 million people in risk of famine. In all these countries, external food aid from global sources is a critical short-term solution to avoid mass starvation. However, the cost of this for the six other countries mentioned above will be over $500 million and is largely paid for by more developed countries beyond Africa. It is sobering to consider that in 2011 over 100 Republican congressional representatives called for the defunding of a principal contributor to such efforts, the U.S. Agency for International Development. Politics and economics far distant from crisis zones of food and water scarcity can have a huge impact. In the longer term, solutions will include locally improved agriculture and water systems, but that is not likely to completely suffice. Food transference, along with maintaining the global political and economic ability for such transfers, will remain a critical component of famine relief and the overall food and water security of the planet. Thus, solutions must also consider a global perspective in terms of the earth’s overall capacity to meet the total food and freshwater needs of over 9 billion people by 2050. This is a challenge that reaches far into the realms of economic, transportation, political, cultural and conflict geography.

There is hope that the food and water challenges we face can be surmounted as we move through the 21st century. It is important to remember that although much remains to be done, there has been remarkable progress made in terms of alleviating global famine over the past 50 years. Up until the 1970’s, great famines killed an average of 1 million people annually and this has declined to as low as 50,000 people today, according to some estimates. Similarly, since 1990, there have been improvements in access to safe drinking water in places such as sub-Saharan Africa where such access has risen from 50 percent to 60 percent of the population. Looking forward, a recent study led by Wolfram Mauser of the Department of Geography at Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Germany and published in Nature Communications estimated that with improved farm management and more efficient spatial allocation of crops, the global food biomass requirements by 2050 could be met even if there was no expansion in world cropland area.

The importance of geography and the geographical perspective in feeding and watering a world population that is climbing to some 9 million people, was recognized in the 2010 National Research Council study “Understanding the Changing Planet: Strategic Directions for the Geographical Sciences.” A chapter was devoted to “How Will We Sustainably Feed Everyone in the Coming Decade and Beyond?”. The chapter outlines the ways in which geographical research contributes to understanding and solving the global food challenges and then posits some critical research questions for geographers. I invite you to read the full chapter for further exposition and consider the research questions raised there. Here I will simply quote the concluding statement:

Sustainably feeding Earth’s population over the coming decade and beyond requires better understanding of how food systems interact with environmental change, how they are connected across regions, and how they are influenced by changing economic, political, and technological circumstances. The geographical sciences’ analysis of food production and consumption, when coupled with recent conceptual and methodological advances, can provide new insights into this critically important research arena.” (p 65).

What role then can the AAG play in furthering this strategic area of geography? We are fortunate to have many talented geographers working across a broad spectrum of the discipline who have direct or ancillary contributions to make in their research, teaching and public communication. We also have specialty groups in Geographies of Food and Agriculture and Water Resources that bring together like-minded geographers to work directly on these issues through research and education. Those working in the geographical tradition of political geography, notably the members of our Cultural and Political Ecology specialty group, have long grappled with the complex environmental and socioeconomic nexus that influences development and sustainability — particularly in the global south. This helps provide a foundation for integrated multi-perspective work. However, I think we can do more to build from this. We can further promote innovative research and educational initiatives on food and water within the dedicated specialty groups mentioned, but we must also work to build even greater linkages to other geographers and our other specialty groups to develop grand and cross-cutting initiatives that tackle the complex environmental, technological, economic, social, political and cultural nexus that is at the heart of providing bread and water for the world’s populations. In such efforts geographical information sciences and remote sensing are key skills that geography brings to bear along with the perspectives noted above. Sessions at our annual meetings and special issues in our journals that seek to tackle these truly grand questions of feeding the world from multiple, but integrated, geographical perspectives form an important pathway. Inviting experts from outside geography to our meetings and to work with us on our research and educational activities will also contribute to this goal. Finally, helping our members share their research and geographical perspectives on world food and water issues with the public, is an important contribution our association can make. The global garden and its fountains are in need of help, and we, as individual geographers and as an association are an important part of the solution.

Join the conversation and share your thoughts on Twitter #PresidentAAG or leave a comment below.

—Glen M. MacDonald

Serving as your President is a singular honor, but also one that is more than a little daunting. My trepidation arises from three sources. First, with the honor of being elected President comes the responsibility to ably serve the aspirations of a wonderful, but large and highly diverse membership. Second, our past Presidents have set a very high bar of achievements against which new incumbents are sure to be measured. These are big shoes to fill. So, before I move on to my third point, allow me to thank the Members of the AAG for their confidence. I also thank our immediate past Presidents Sarah Bednarz, Mona Domash and Julie Winkler for the inspiration and warm friendship they have provided. In the end, all I can promise is that I will do my very best to serve all our Members and further the legacy of our past Presidents. What I would ask in return is that you share your ideas and experience with me. Be sure to let me know if I miss an important concern or stray off course in addressing such issues. I am very teachable.

Serving as your President is a singular honor, but also one that is more than a little daunting. My trepidation arises from three sources. First, with the honor of being elected President comes the responsibility to ably serve the aspirations of a wonderful, but large and highly diverse membership. Second, our past Presidents have set a very high bar of achievements against which new incumbents are sure to be measured. These are big shoes to fill. So, before I move on to my third point, allow me to thank the Members of the AAG for their confidence. I also thank our immediate past Presidents Sarah Bednarz, Mona Domash and Julie Winkler for the inspiration and warm friendship they have provided. In the end, all I can promise is that I will do my very best to serve all our Members and further the legacy of our past Presidents. What I would ask in return is that you share your ideas and experience with me. Be sure to let me know if I miss an important concern or stray off course in addressing such issues. I am very teachable. Perhaps nothing illustrates the opportunities and challenges we face better than circumstances during my writing of this column. At present I have the benefit of writing on a computer designed in the United States and assembled in China. The computer is networked via fiber optics to the UCLA library system. I am, however, 400 miles away from UCLA at an elevation of just over 8,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada of California. Thanks to a small satellite dish I have been able to watch the BBC News from London while I work. What I have been watching is the vote by the United Kingdom to try and turn back the tide of globalization by exiting the European Union. Almost instantly stock markets around the world, including the Dow, plummeted in response to the potential economic and political implications. A truly globalized experience. However, within the UK the vote was strongly geographically structured with Scotland, Northern Ireland and London being against the exit. Scotland is now considering a second referendum on independence from the rest of the United Kingdom. This could split the nation along clear geographic lines. The strong exit vote in England and Wales was driven by a geographically prescribed sense of British (English largely) identity, a reaction against elites and intellectuals, disdain for increasing EU regulations, including environmental ones and fears about an influx of refugees from civil war, the depravations of ISIS, and lack of food and water in Syria and adjacent refugee camps some 2,500 miles away. None of this is understandable or will be manageable without consideration of geography. It demonstrates the forces of both global connectedness and global geographic diversity operating on multiple scales.

Perhaps nothing illustrates the opportunities and challenges we face better than circumstances during my writing of this column. At present I have the benefit of writing on a computer designed in the United States and assembled in China. The computer is networked via fiber optics to the UCLA library system. I am, however, 400 miles away from UCLA at an elevation of just over 8,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada of California. Thanks to a small satellite dish I have been able to watch the BBC News from London while I work. What I have been watching is the vote by the United Kingdom to try and turn back the tide of globalization by exiting the European Union. Almost instantly stock markets around the world, including the Dow, plummeted in response to the potential economic and political implications. A truly globalized experience. However, within the UK the vote was strongly geographically structured with Scotland, Northern Ireland and London being against the exit. Scotland is now considering a second referendum on independence from the rest of the United Kingdom. This could split the nation along clear geographic lines. The strong exit vote in England and Wales was driven by a geographically prescribed sense of British (English largely) identity, a reaction against elites and intellectuals, disdain for increasing EU regulations, including environmental ones and fears about an influx of refugees from civil war, the depravations of ISIS, and lack of food and water in Syria and adjacent refugee camps some 2,500 miles away. None of this is understandable or will be manageable without consideration of geography. It demonstrates the forces of both global connectedness and global geographic diversity operating on multiple scales.