Attracting students of all backgrounds to programs in geography or geocomputation starts before they enter college

By Coline C. Dony, Atsushi Nara, Michael Solem

Faculty at geography programs in the U.S. regularly reach out to the AAG to ask which strategies they can use to attract more students, and especially how to reach students who have been underrepresented in their program(s). AAG worked on projects and efforts over the years to help us answer these questions, such as the ALIGNED project, the Enhancing Departments and Graduate Education (EDGE) in Geography initiative, and the Diversity Ambassadors program. Some of our past efforts also generated resources (e.g., a few books from the EDGE project) and advanced conversations on these challenges (e.g., during sessions at our Annual Meeting). What these efforts have not been able to do yet is measure our overall progress toward including more perspectives and identities in our geography community and the effectiveness of certain strategies.

General observations from AAG members (and from AAG staff), however, are that even if some progress toward diversity and inclusion (D&I) is visible, it is not sufficient, and it has been too slow. First, if we want to move past a “general observation,” we need to better measure where we are today, and systematically measure our progress toward attracting the next generation of geographers. The AAG D&I Committee recognizes this too, and has recommended “Enabling Data-Driven D&I Excellence” in the 3-Year Justice, Equity, Diversity & Inclusion Strategic Plan released in October of 2021. Second, if progress has been too slow, we may need to recognize that the strategies we have used thus far may not be as effective as we think, or may not have addressed challenges at their root.

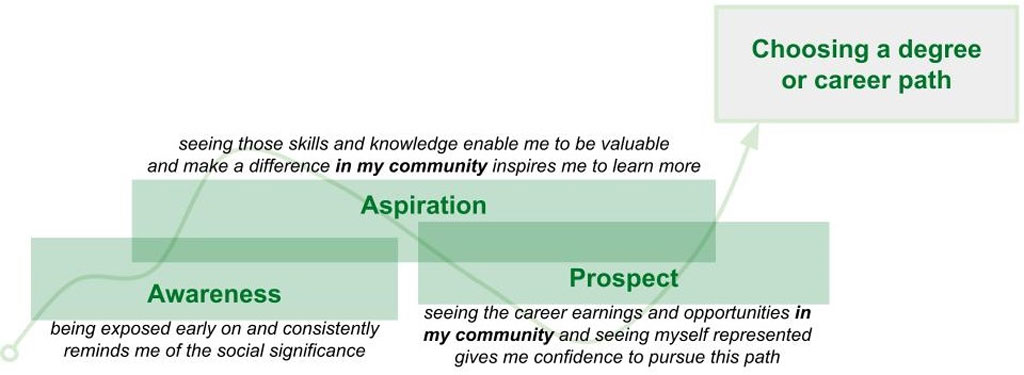

Low enrollment in U.S. geography programs is mainly caused by the lack of awareness among incoming college students that geography is a discipline and a career pathway. This lack of awareness can then contribute to the lack of diversity in our programs. Here is one example how: Because of their lack of geography awareness, college students who do “discover” geography, only do so after a year or two into their studies (if they happen to take a geography course, for example). Even if that course inspires them to pursue geography, by that time, students typically already have their major declared. At that point, it can be a hard financial case to make to change majors or to add a minor or certificate. If good career earnings are not obvious on top of that, or if students do not see themselves represented among professions, the case to switch majors becomes even harder, particularly for those already underrepresented. For that reason, it becomes especially important to raise the awareness of students who are underrepresented before they enter college.

Figure 1: Choosing a degree or career path is a careful consideration (particularly for underrepresented groups) that starts with being aware of possible paths. Awareness can develop into an aspiration to pursue one or more paths if it is clear the skills and knowledge will help make a difference. The clear prospects (careers and representation), however, weigh heavily in our choices.

Figure 1: Choosing a degree or career path is a careful consideration (particularly for underrepresented groups) that starts with being aware of possible paths. Awareness can develop into an aspiration to pursue one or more paths if it is clear the skills and knowledge will help make a difference. The clear prospects (careers and representation), however, weigh heavily in our choices.

That lack of awareness among college students about our discipline and its career opportunities is rooted in the limited geography instruction in the U.S. school system. The focus of instruction in K-12 is on reading, math, and science, with a more recent push to make space for computer science instruction at all levels. Geography, on the other hand, is not a subject that is required (nor high in priority) in most states. In their consistent Survey of Social Studies and Geography in Middle and High Schools, the Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education reported that in 2020-2021 only 4 states required a stand-alone geography course in middle school (down from 16 in 2009-10) and 11 states required a combined geography and social studies course. From the same report, only 3 states required a standalone geography course for high school graduation (down from 6 states in 2009-10) and 10 states required a combined course. The remaining states either do not require geography or offer geography as an elective course.

When geography is not offered as a stand-alone course, it typically finds a small space in the social studies curriculum. In “Most Eighth Grade Students Are Not Proficient in Geography,” the Government Accounting Office reported in 2015 that over 50% of teachers who spent 3-5 hours per week on social studies instruction spend 10% or less on geography. Given the pressure new subjects add to instruction time (e.g., Computer Science), geography finds itself in a perennial struggle for curriculum space. Keep in mind too, that most teachers instructing social studies or stand-alone geography courses do not have a background or degree in geography.

If we want diverse youth to come to college campuses with an awareness and aspiration to study geography, then we need to find effective strategies to foster that awareness and aspiration at the K-12 level. Some geography programs already recognize this and have developed connections with local schools (e.g., by inviting their students to their campus, organizing a GIS day, or spending a few days in local schools to help with geography instruction). These efforts are important, but faculty often lack sufficient time to invest in these events on a consistent basis. By the time a student applies for or starts college, the geography event(s) they participated in may no longer sit fresh in their memory.

If anything, geography teaches us that our local context matters, and it helps us connect to concepts, even if they are complex.

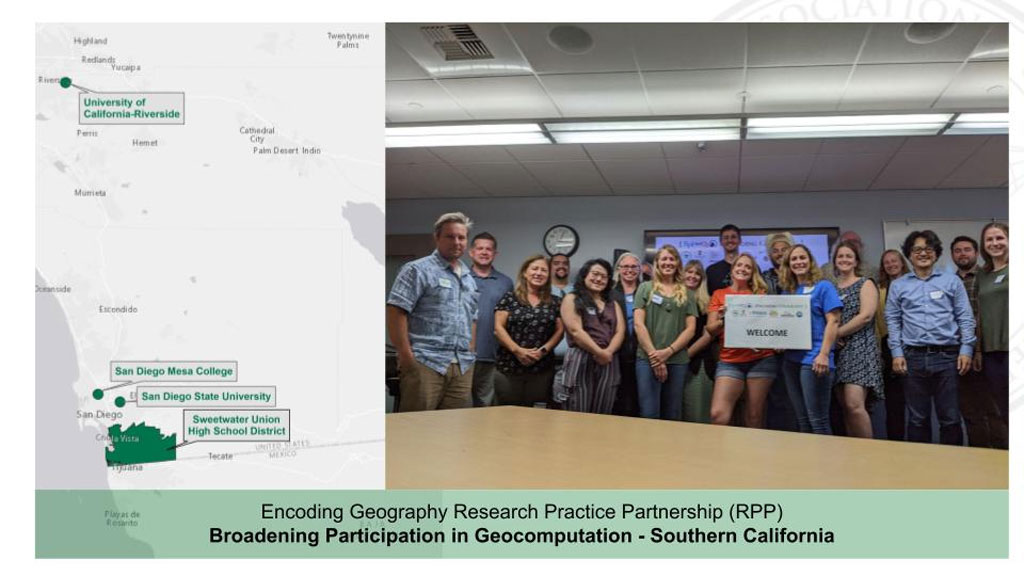

Under our Encoding Geography initiative, the AAG initiated a collaboration in 2018 that now includes 2 universities (San Diego State University [SDSU] and University of California Riverside), a community college (San Diego Mesa College [SDMC]), and a high school district (Sweetwater Union High School District [SUHSD]), all in Southern California. The goal is for students of all backgrounds to find geography more consistently along an inclusive curriculum pathway connecting multiple levels of education. Initiating sustainable collaborations across educational levels and institutions is complex, which is why we follow both the Research-Practice Partnership (RPP) approach and the Collaborative Impact Framework, which recommends “backbone” organizations. The stakeholder organizations supporting this collaboration are the AAG, the National Center for Research in Geography Education (NCRGE), and the California Geographic Alliance (CGA).

This summer, this Encoding Geography RPP organized a workshop at SDSU for instructors (high school and college) that are already along students’ pathway towards careers in geography, namely instructors of geography, GIS, and computer science courses in SUHSD and SDMC. Indeed, in the local context of California, geography careers in the tech sector are numerous and require a combination of geography and computer science skills and knowledge (which we refer to as “geocomputation”). One advantage we have in the SUHSD is that geography is a standalone and required course, which means there are geography teachers, and all high schoolers have an opportunity to learn geography. Then, working with computer science teachers to incorporate spatial thinking in their courses creates additional places for students to learn about geography. During the workshop, we engaged in discussions and activities around geography, spatial thinking, computational thinking, and geocomputation. To set the stage for these discussions, Kelly León, a doctoral student in education for social justice at SDSU and geography teacher and cohort leader at SUHSD, coordinated a virtual series of Teacher Professional Learning earlier this Spring.

Figure 2: Map showing the locations of the educational institutions participating in the Encoding Geography Research Practice Partnership (left) and a picture taken at the workshop organized at San Diego State University (SDSU) in August 2022 (right).

The workshop also covered ways to build awareness, develop aspiration, and show degree or career prospects, which are the main elements needed for students to choose a degree or career. The Powerful Geography approach to teaching and learning helps combine those elements in the classroom. It takes into account principles of culturally/community-driven teaching to help student aspirations, and it recognizes that students change every cycle while their local context also changes (e.g., local workforce needs, and social challenges) which means instructors are best positioned to adapt lessons that will develop their aspirations. Too often, we see solutions in the form of pre-packaged lessons with the intent to save instructors’ time. Yet, these lessons can completely miss the local context and can disempower instructors and make them lose confidence in the pedagogy experience and expertise they bring. If anything, geography teaches us that our local context matters, and it helps us connect to concepts, even if they are complex.

The participating instructors in our workshop will help us this academic year to collect baseline data about their students’ awareness and aspirations around geography, computer science, and geocomputation. Next summer, they will participate in a lesson development workshop and implement their lessons in their classrooms. We will collect data again to measure the impact of these lessons on their students’ awareness and aspirations. Because of the National Science Foundation’s interest in research on strategies to broaden participation in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), its CSforAll program is funding our collaboration (NSF Active Award Nos. 2031418, 2031407, and 2031380. Past Award No. 1837577).

Recognizing that teachers don’t always come with a background or degree in geography or computer science, we are also measuring how their involvement in Encoding Geography impacts their awareness around these concepts. Participating instructors in this project will receive more professional development opportunities from our partners to continue building the strength of this RPP. For example, more virtual professional development series are planned by SDSU and SDMC this Fall. Additionally, the Center for Human Dynamics in the Mobile Age at SDSU (directed by Professor of Geography Ming-Hsiang Tsou) has been organizing the “Big Data Hackathon\San Diego” for a few years now. This year geography and computer science teachers were invited to help coordinate activities for the hackathon to give them additional ways to keep engaged on geocomputational challenges. On the long run, strengthening these connections may help attract more high school students to participate in the hackathon, adding an additional space for students to build awareness, develop aspiration, and see prospects to choose a degree or career path in geography or geocomputation.

At the upcoming AAG Annual Meeting in Denver (March 23-27, 2023), we will organize panels to discuss strategies to create inclusive pathways for geography from schools to colleges. If you are at a community college or university and you are in the process of building connections with local schools, or you already built some connections, we invite you to participate in one of our panel discussions. If you are interested, please contact Julaiti Nilupaer, our AAG Research Assistant, at [email protected], who can provide more details and will coordinate the organization of those panels.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0116