A Glance at New Orleans’ Contemporary Hispanic and Latino Communities

Situated near the mouth of North America’s largest river, New Orleans has long served as a major port that advantageously connects the United States’ heartland to the rest of the world. Proximity and access to the Gulf of Mexico strategically place the Crescent City between the large consumption economy of the United States and the extraction economies of Latin America, which have historically been key purveyors of raw materials and commodities to the markets of their northern neighbor. Also, New Orleans served as a jumping off point for numerous military expeditions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that altered the political landscape of Latin American countries. Yet, even before becoming an “American” city, New Orleans was governed by the Spanish via Cuba (1762―1803). These economic, political, and historical linkages to Latin America and beyond have facilitated the transnational flows of people, products, and cultures over the course of four centuries and have cultivated the unique multinational ethnic kinship the port city holds today with Latin America and Spain [1]. Evidence abounds of these Hispanic and Latino ties in the cultural landscape, especially in one of the Big Easy’s most notable cultural productions: music [2]. Similarly, visitors with a keen eye will be able to discern the Latin American imprint woven into the urban fabric stretching from the French Quarter to the western suburb of Kenner and the riverbanks of St. Bernard Parish [3].

Contemporary Latino migration and settlement in the southern United States have received considerable scholarly attention―particularly from geographers―over the past three decades. The “Nuevo South” moniker was coined to describe this supposedly new migratory phenomenon taking place. However, before Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans was often left out of discussions on southern destinations for Latinos, even though it was home to one of the oldest and most diverse Latino populations in the country. Perhaps the lack of attention was because the metropolitan area’s Latino population was relatively stable and mostly integrated. Of the 58,545 Latinos enumerated in Census 2000, four out of five were U.S citizens, more than half were born in the United States, and Latino household incomes were only slightly below the region’s average [4]. Therefore, New Orleans’ Latinos didn’t fit the narrative of a “New Latino South” so often applied to describe emerging Latino communities made up of and sustained by recent immigrants looking for new opportunities. But, in the wake of Katrina, New Orleans gained national attention seemingly overnight as Latino immigrants from Mexico, Central America, and as far away as Brazil and Peru flocked to southeast Louisiana to participate in the reconstruction efforts. Many arriving laborers were undocumented, taking advantage of the temporary suspension of federal and state enforcement of employment eligibility verification. While a study conducted by scholars from Tulane and Berkeley estimated that 14,000 Latinos laborers arrived within the first few months after the storm, local community leaders, social workers, and others engaged in the reconstruction efforts suggested much higher figures. In any case, this demographic phenomenon caught the attention of local officials, denizens, and national media. A Newsweek article posed the question, “Will Latino day laborers locating in New Orleans change its complexion?” [5]. Then-mayor Ray Nagin infamously asked himself in front of a town hall audience, “How do I ensure New Orleans is not overrun with Mexican workers?”. Indeed, Latinos became a prominent fixture in the metropolitan area in the years following Katrina. As laborers gutted and rebuilt flooded homes, taco trucks appeared throughout the city, and new tiendas, taquerías, pupuserías and Latino-themed night clubs opened across Orleans and Jefferson Parishes. Likewise, numerous Latino-focused nonprofits and religious organizations launched legal and language services designed to help arriving Latino immigrants settle and integrate into southeast Louisiana.

New Orleans certainly emerged more Latino than before the storm. Census 2010 counted 91,922 Latinos in the seven-parish metropolitan statistical area―an increase of 57 percent since 2000. But, as reconstruction effort came to an end, the surge of Latino workers that arrived after Hurricane Katrina appears to have receded. According to the Mexican consulate―which reopened in New Orleans in 2008 amid a new demand for administration and diplomatic functions for Mexican nationals in Louisiana and Mississippi―consulate employees were handling 80 to 100 appointments a day in the first years after the storm. Lines regularly formed outside the consulate’s location in the central business district, as Mexican immigrants waited to renew passports or matriculas, or to access other services. A decade later, however, appointments average between ten and fifteen daily which has led the consulate to scale back its number of employees. As demand for construction workers declined, some Latino laborers moved elsewhere within Louisiana such as Baton Rouge, Gonzales, and Alexandria while others relocated to states like Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia and Florida and still others returned to their countries of origin.

Although the initial intensity of post-Katrina Latino migration may have subsided, it certainly reinvigorated existing Latin American communities. This is most evident in the metropolitan area’s four core parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard, and Plaquemine which are home to 76,129 Latinos as identified by Census 2010. The settlement and integration of post-Katrina Latinos have put new emphasis on Latin American culture, which has led to new restaurants, stores, festivals, and radio programs that cater to an established ethnic community. Yet, many of the new Latino establishments have found success serving a larger non-Latino clientele. For example, David Montes de Oca, a Mexico City native, came to New Orleans via Houston with a taco trailer in tow. His first patrons were day laborers living and working in suburban Jefferson Parish. Yet in 2007, Jefferson Parish officials began passing measures to restrict street venders. Montes de Oca responded by opening a brick-and-mortar restaurant called Taquería Chilangos in a shopping center home to other Latino-owned businesses in the 2700 block of Roosevelt Boulevard in Kenner. Taquería Chilangos built a strong customer base by serving typical Mexican fare and earning a reputation for the best authentic tacos in New Orleans. Another example is Norma’s Sweets Bakery at 2925 Bienville Street in New Orleans’ Mid-City neighborhood which opened following Katrina to serve the growing number of Latino residents in the area. The bakery’s menu includes a variety of Latin American pastries and lunch options, but Norma’s Sweets becomes a favorite destination for non-Latino customers during Carnival season for its Cuban-style king cake filled with cream cheese and guava paste.

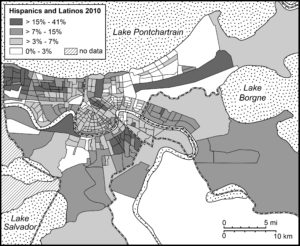

Perhaps one of the more interesting facets of New Orleans’ post-Katrina Latino geographies is the resurgence of Honduran population. New Orleans and Honduras share a long history starting with the once-ripe banana trade. The port city also served as a gateway for Honduran immigration. By the mid-twentieth century, Honduran immigrants residing in the Lower Garden District’s Irish channel neighborhood reached a critical mass, and, within the Latino community, the area became known as the Barrio Lempira (named after Honduras’ currency). By the 1960s and 1970s, upwardly mobile Hondurans were moving to the Mid-City neighborhood and by the 1980s and 1990s many relocated to suburban communities of North Kenner and Metairie in Jefferson Parish. Although the mid-century decennial censuses did not disaggregate persons of Honduran origin, Hondurans were considered the prominent Latin American nationality in the metropolitan area―so much so that erroneous claims of mythic proportions stating that 100,000 Hondurans lived in New Orleans or that New Orleans was home to largest the Honduran community in the United States, became commonplace. Of course, later censuses that enumerated Hondurans proved these assertions false. Census 2000 counted only 8,112 Hondurans in the metropolitan area, more than two-thirds of which were found in Jefferson Parish. In fact, the metropolitan area’s Mexican population had grown larger, numbering 10,202. But following Katrina the number of Hondurans soared. By 2010, Hondurans could accurately claim to be the largest Latin American nationality with a census count of more than 25,000—around 4,000 more than the enumerated 20,729 persons claiming Mexican origin at that time. Although visible residential and small business clusters are found in Jefferson Parish, which is now home to three-quarters of the area’s Honduran population, many newcomers settled in other sectors of the metropolitan area, even venturing into eastern New Orleans neighborhoods like Village de L’Est home to the city’s Vietnamese community and extending as far as St. Bernard Parish. (Figure 5)

Today New Orleans’ Honduran identity and sense of place manifest themselves in various ways. St. Teresa de Avila Catholic Church on Erato Street, which served the Hondurans and other Latin Americans Catholics who lived in the Barrio Lempira, features a statue of Our Lady of Suyapa, the patron saint of Honduras. The church hosts an annual festival in her honor on February 3rd celebrating the virgin as does the Immaculate Conception Church in Marrero on the West Bank where children perform national dances in traditional dress. More frequently, Hondurans gather each weekend in public parks, most notably City Park in Mid-City, to play soccer. For those looking for authentic Honduran cuisine, numerous restaurants can be found throughout the metropolitan area; however, Casa Honduras at 5704 Crowder Boulevard in New Orleans East is noteworthy. Not only does Casa Honduras offer typical Honduran dishes, it serves traditional Garifuna food and drink such as sopa de caracol con coco (coconut curry conch soup) and gifiti (a drink made with rum, herbs, and spices). Casa Honduras has become a de facto cultural center for New Orleans’ Garifuna community and periodically hosts Garifuna musical performers and events [6]. For visitors interested in Afro-indigenous culture from Central America, a meal at Casa Honduras is worth the trip.

Despite Hondurans being the largest Latino group in the metropolitan area, they account for only a little more than a quarter of the total contemporary Hispanic and Latino population. New Orleans has long been home to an assorted Latin American population. Through commerce, social networks, and geopolitics, or due to natural disasters, different groups have arrived to make the city their home, beginning with Los Isleños who first settled in the area in 1778. Indeed, most groups are less conspicuous when compared to the Hondurans and Mexicans, yet they have all contributed the creation of a distinctive pan-Latino identity in the city. While some national-origin groups populations have waxed and waned through the years, others have continued to grow. Between 1980 and 2010, the number of Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans doubled, and the number of Cubans has slightly increased to 6,440 since 2000. Brazilian immigration to New Orleans began with the coffee trade in nineteenth century. The number of Brazilians in the city, however, was small until post-Katrina reconstruction efforts attracted thousands of Brazilians from other U.S. cities like Boston and Atlanta as well as Brazil. The surge was brief, and many Brazilians left within the first few years following the storm. Nevertheless, those who stayed have established a Brazilian community anchored in Kenner and Chalmette in St. Bernard Parish. A notable establishment for those seeking authentic Brazilian fare such as Feijoada is the Brazilian Market and Café at 2424 Williams Boulevard in Kenner.

While each national-origin group seeks to maintain its own traditions and character, a pan-ethnic identity has emerged to unify those of Hispanic and Latino heritage. Media outlets such as Jambalaya News, Radio Tropical Caliente, and LatiNola.com provide news and entertainment programming in Spanish and work to connect local Latinos with the larger New Orleans community. The Hispanic Heritage Center sponsors Latin American-themed cultural activities and artists in the region and provides scholarships to promising Hispanic high school students. Other annual Latino festivals like Que Pasa Fest, Kenner’s Hispanic Summer Fest, and Carnival Latino attract large numbers of both Latino and non-Latino visitors. Finally, nonprofit and religious organizations like Puentes, Congreso de Jornaleros, and the Archdiocese of New Orleans Hispanic Apostolate advocate on behalf of Latino immigrants (particularly undocumented) and, in turn, help to foster a stronger sense of a pan-Latino community. Thus, as the composite and size of New Orleans’ Hispanic and Latino community will undoubtedly continue to fluctuate, it will remain a significant and dynamic component of New Orleans’ society and unique culture.

— James Chaney, Middle Tennessee State University

[1]. “Hispanic” designates an individual or group of Spanish-language heritage. “Latino” identifies an individuals or groups from Latin America of Spanish- or Portuguese-language origin. For a more detailed analysis of New Orleans’ Hispanic and Latino populations and heritage see Hispanic and Latino New Orleans: Immigration and Identity since the Eighteenth Century. (2015) Andrew Sluyter, Case Watkins, James P. Chaney, and Annie Gibson. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press

[2]. See Case Watkins’ two-part essay Essential Geographies of New Orleans Music in the September 2017 AAG Newsletter for an overview of the evolution of New Orleans’ music culture. DOI: 10.14433/2017.0013

[3]. For a little help finding and understanding New Orleans’ Hispanic and Latino landscapes see Andrew Sluyter’s article in the August 2017 AAG Newsletter. DOI:10.14433/2017.0011

[4]. Anita I. Drever (2008): New Orleans: a re-emerging Latino destination city, Journal of Cultural Geography, 25(3): 287-303. DOI:10.1080/08873630802452632

[5]. Arian Campo-Flores (2005) A New Spice in the Gumbo: Will Latino Day Laborers Locating in New Orleans Change its Complexion? Newsweek. 147(23): 46.

[6]. The Garifuna (or more correctly the Garínagu) are mixed-race descendants of African, Island Carib, European, and Arawak peoples who are found mainly in Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, Guatemala, the island of St. Vincent and, since the twentieth century, the United States. For more information about New Orleans’ Garifuna community see James Chaney (2012) Malleable Identities: Placing the Garínagu in New Orleans. Journal of Latin American Geography 11(2): 121-144. DOI:10.1353/lag.2012.0049